I spent a month in Cairo in June 2014. The main objective of my trip was to test the feasibility of what I had in mind-as outlined in Version 1 of this project-to tamper with my preconceptions, to debacle my confident plans. Indeed, I partially succeeded in my feat of self-deconstruction.

I was left bewildered by the complexity of the situation, the liquid forms of public and private space that exist on the island of Gezirat al-Qursaya, and in the city of Cairo at large. Yet unanswered questions on the nature of representation tore through the tense atmosphere of military rule.

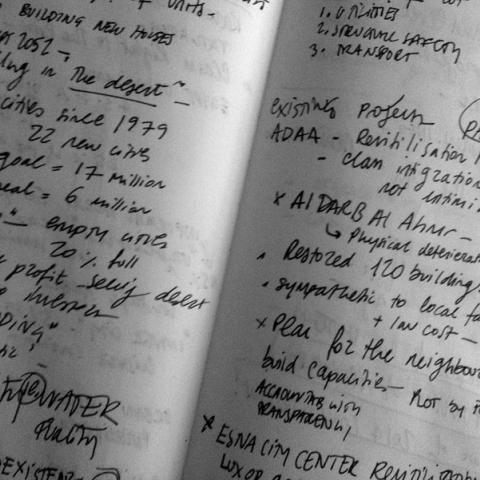

Here, in the second phase of research for this project, I share a soundscape made from clippings of different meetings and interviews conducted in the city, as well as a mindmap I drew roughly two weeks after I had left Cairo in an attempt to trace what had made a mark. Below are a brief text and a set of images from this second research phase.

A small boat attached to a pulley takes you across the tiny stretch of Nile that separates Qursaya from Cairo proper. A young man tugs at the chain that drags the makeshift transport vessel across for half a dinar, dropped loudly into a tin can. Once on the island the quietness hits you, the roaring traffic has surprisingly shrunk to a hum or a halt. Three dirt roads roughly a foot across take you either towards a densely populated strip with 3 storey buildings made out of breezeblocks and plastered with colour, or down to Dr.Mohamad's house, or towards a small banana plantation. These are the endpoints of my journeys, between them lie a host of smaller houses and fields, tended to by families who claim to have lived here for 300 years.

The majority come from Al-Dahab, the larger neighbouring island. They used to row to Al-Qursaya when the tides were low to farm it. The Aswan dam was built and Qursaya revealed itself entirely, becoming Land. Some say it happened in 1902, others insist it was later, in the 50s when the Higher Dam was built.

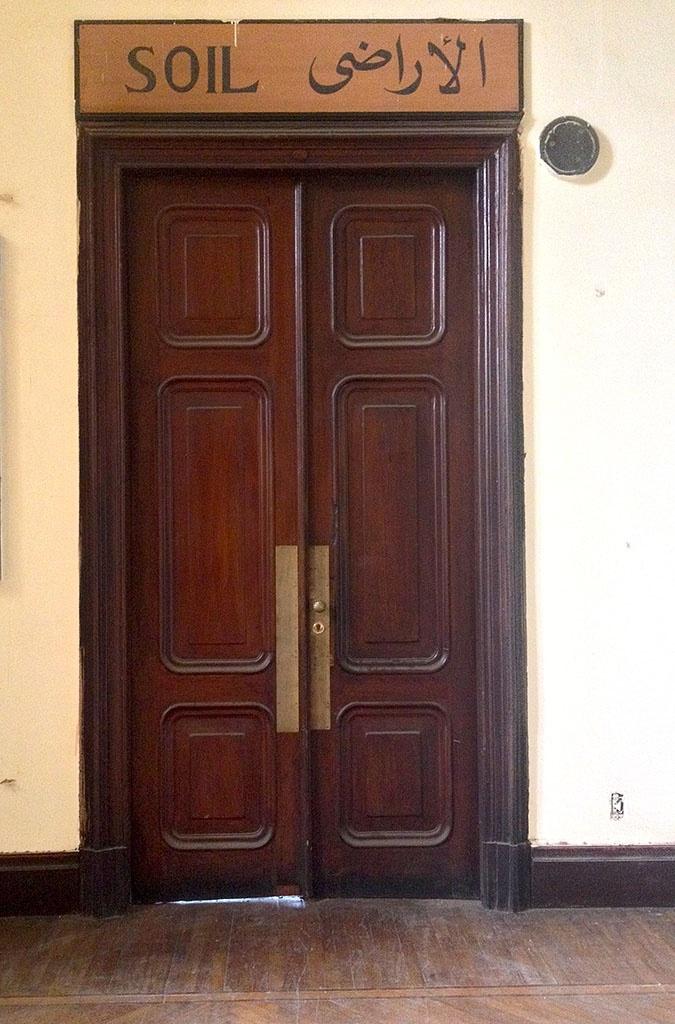

At the Agricultural Museum in the Doki neighbourhood of Cairo, an attendant turns on the neon lights in the vitrines just for us. The vitrines host complex woodcarvings of landmasses, the descriptions hand painted onto the undulated surfaces. The construction of the Aswan Dam is a large-scale diorama lit in pastel hues with small buildings exuding a fiery light. I think to myself that it could be a model from the 1972 film Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky. The museum was opened in 1938 and it now appears like a giant obsolete 3D encyclopaedia, full of plainly explained scientific fact based on the life of local fish and amphibians, bakers, market-goers and their families. It is on the verge of disrepair, some of the stuffed plovers are beginning to rot. A man waxes the floor constantly to an impeccable finish.

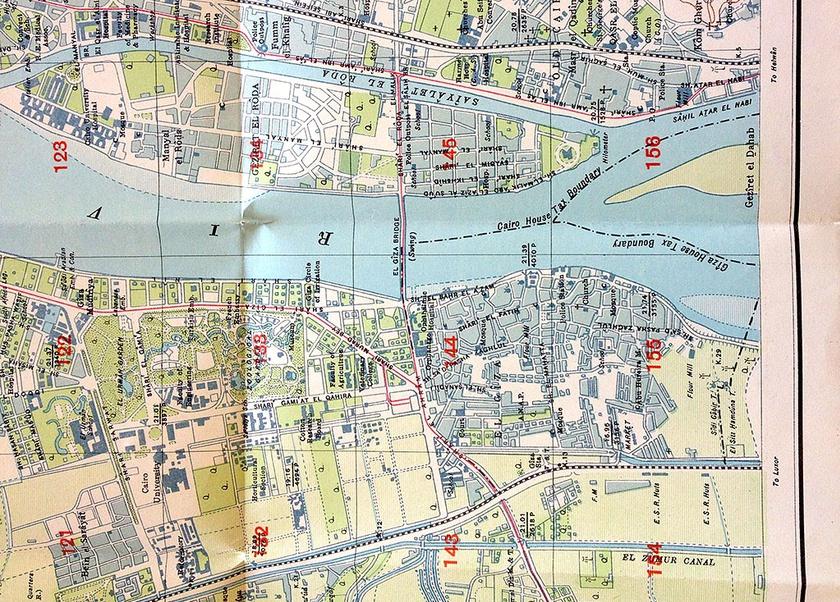

I look for maps of the island at the American University of Cairo library but none seem to exist. The island only appears in newer city street guides where the metropolis is divided into brightly coloured segments marked by ciphers running across the page edges. Only one of these guides names it, in all other material, including Google maps, the island is a blank slate. All maps preceding the 1970s stop at Al Rawda, the last formally settled island south of the city-centre.

The southern tip of the island, past the densely populated settlement is home to the Pharaonic Village. The Village is a tourist attraction built to resemble various facets of life under the Pharaohs. Tableauxs-vivants illustrate ancient crafts that actors play out on repeat with evident boredom. I later find out many of the actors employed by the Pharaonic Village live across the wall, in the occupied part of the island. I am fascinated by the scene being acted out which describes the first methods of taxation implemented by the State.

We return to the island almost daily. Sometimes in the mornings when the fishermen return from their trips at dawn, sometimes in the evenings to find and talk to those who leave the island for work in the city. Our conversations are long and often begin with an invite to join a family in their home. I ask about their land, what it means to them, how it was gained and may be lost. Many claim they own the land and have recently received deeds through a court battle; some still rely on the encroachment law which allows them to live on the island by paying a small rent to the ministry of agriculture. After the last attempted military occupation which left one dead the topic of the military's claim to ownership of the island for 'defence purposes' is a clear point of contestation.

On Tuesday we walk down towards to the northern tip of the island, on the way there we see holiday homes shut and barred, then some large skeletons of unfinished buildings as we reach the banana plantation. A group of men seem to be harvesting in neat lines whilst others overlook the scene. We are approached by two of them, they ask us who we are, not at all amused by our presence, and I pause to think of an answer. I see their khaki coloured tents firmly fixed on a clearing. It becomes increasingly clear they are soldiers occupying that slither of Qursaya. We are told to leave the area.

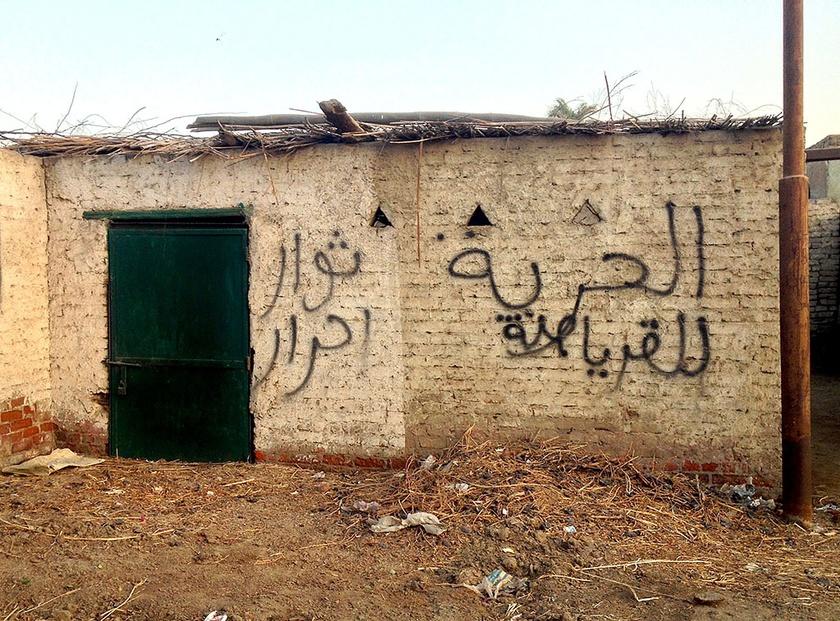

The incident leads me to consider the nature of recording under a military state. What does it mean to record now on the island? What devices, more and less inconspicuous, produce a different set of relations between the one behind and the one in front of the lens under these conditions? The Military State becomes present at the sight of a recording device which is immediately redolent of a set of threats. How can one record when the recording device directly acquires the tone of a weapon? I think of black screens, of removing context, of removing image, until there is nothing left to suggest a space or a person proper. I think of not recording; but then, why am I here?

The night we first meet she is restless. While I talk her through my ideas I feel belittled by her worry. She is not listening, and rightfully so; friends have been arrested at a protest again, and now that the anti-protest law is in place this could mean anything.

*-*

On our last visit to the island we cross a side street behind the mosque. Perched on a knoll buttressed by the roots of an ancient tree lies a small 2 storey house. The intricate ceramic tiles on the floor give away its age. It is the oldest house on the island and those who live there are it's oldest settlers. The house was built when the island was not yet Land. The house was built when the Nile rhythmically swallowed up the fields tended to by this family.

In 2050, according to the CGI model called 'Cairo Urban Dream', grand boulevards shrouded in mystic light resembling a landing strip for UFOs will be built nearby. The capital will officially become a 'Global City', finally hosting its delirious set of skyscrapers, high-end riverside condos and banalised plazas, free of riff-raff and tuc-tucs. Qursaya will become 'The Cloud Recreational Project', a set of 'public' parks, surrounded by luxury development. The presentation is over, the officials stand, the last page of their Powerpoint reads: Thank You, Nothing is impossible, as long as there is Will, Desire, and Future Vision.

About the artist

Adelita Husni-Bey is an artist and researcher. Born to an Italian journalist and a Libyan architect in 1985, Adelita studied Fine Art at Chelsea School of Arts and Photography and Sociology at Goldsmiths University. Her practice, which encompasses drawing, painting, collage, video, and participatory workshops, concentrates on micro-utopias, and on how collective memory works, as well as questioning the mechanisms of political and economic power and control.

Her background in sociology as well as fine arts aided her in her critique of prevailing systems of organization of advanced capitalist societies, in areas such as labour, schooling and housing. She questions the type of visibility present in the production of artwork about 'under-represented communities' and looks for alternatives, as a form of reaction to the way Western society is structured. In that sense, her role as an artist strives to instigate reflection on, and effectively produce, alternative social imaginaries.

Recent projects have also focused on unearthing and re-thinking radical pedagogical models within the framework of anarcho-collectivist studies. Her solo shows have included The Green Mountain, ViaFarini/DOCVA, 2010, Deadmouth at Galleria Laveronica, 2010, Playing Truant, Gasworks, 2012. Selected group shows include: TRACK, S.M.A.K museum, 2012, Mental Furniture Industry, Flattime House, London, 2013, Jens, Hordeland Kunstsenter, 2013, Meeting Points 7, MuKHa, Antwerp, 2013, 0 Degree Performance, Moscow Biennial 2013, What is an Institution? Beirut Season 4, Cairo, 2013, We Have Never Been Modern, Songeun Art Space, Seoul, 2014, Giving Contour to Shadows, Neue Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin, 2014, Utopia for Sale?, Maxxi Museum, Rome. She has been featured in International Art-related press such as Flash art, Modern Painters, Ibraaz, Mousee Magazine and Frieze, as well as international newspapers The Guardian and Corriere Della Sera. She has recently completed the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York and is working with Italian schools to foster a critical understanding of the economic crisis by teenage students.