This is my arrival scene, in October 2014 and the air is tense yet again. We're behind on most fronts. My research assistant has rightly moved on to better and bigger things, so I am scrambling to put our work together, now much more informed, yet still lost in and (round)-about the mega-urban plan: Cairo 2050. I have spent the summer months dwelling on Habitat International conference papers, re-visiting David Harvey's 'Acccumulation by Dispossession', pouring over laws and articles, and generally wondering what it would mean to commit all this to film; and how.

On my way to Cairo I somehow found Salma, through Facebook contacts. We meet and she takes me out behind Talat Harb to eat Hammam Mahshi. While sitting at the table she instructs me on how to pop the pigeon's ribcage open and expose the rice. Salma has been my beacon of light in rather turbolent times, she has formed a small team of activists and researches who will help us string our ideas together. I'm glad we share the urgency of this work but there's always an unbridgeable distance between someone who will leave a place, and someone who will stay. It's a dry riverbed between our current life choices we won't fill. It's my cop out, the travelling art precariat, and it makes me feel out of place.

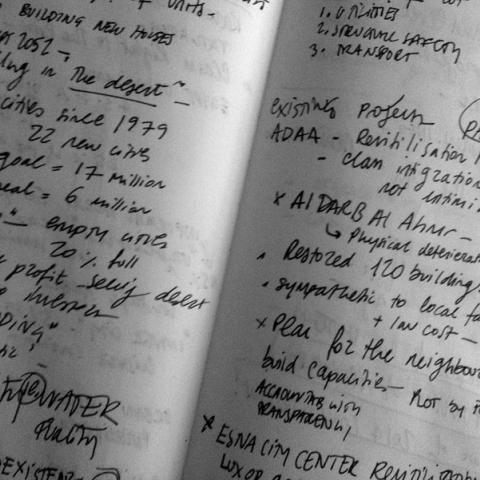

She offers her apartment, on the dusty top floor of a towering building, as our base. We spend many hot afternoons with the curtains drawn laying on pillows, stretched out on the floor, leafing through maps, plans, lists, questions. Occasionally we look outside onto Tahrir square. Many times our conversations are interrupted by thoughts of what real momentum felt like, and by Salma's acquaintances visiting briefly – not to remember with nostalgia (that is simply too painful) – but to attest to the possibility of emotional survival: that getting ripped apart by depression is not the only option. That's what it's come to.

Nazly is going to run the workshop, my Arabic is not up to scratch and it will be distracting. Nazly has already worked on the island, and was even mentioned in a military conference held on Qursaya a few months prior. We find the conference video on YouTube: "this activist has come to show the kids on Qursaya how to hate the military, they now draw tanks and spitfires aimed at the servicemen!" We place the cursor back and ape the General. We laugh out loud.

With this sort of crew it is neither safe nor wise to film on the island proper, so we decide to film in a theatre. After all, I feel the island will only serve as a backdrop or prop, whereas it is so much more central, so central it can be imagined through speech. We visit a few spaces, including a dance rehearsal studio on the 5th floor of a downtown building, where teens are intent on learning a new Beyoncé routine, stretching legs up high on the barre. We settle for Rawabet theatre, the height of the ceilings, the largeness of the space will allow us to be flexible with shooting angles while not disturbing the workshop.

Through further conversation we eventually find working on the case of the island alone might be reductive of the larger demolition plan embodied by Cairo 2050. The recently passed 'Public Benefit Law' details how entire neighbourhoods might be taken down because of 'aesthetic considerations' tied to the plan and this will effect most informal settlements in the city. Furthermore the Qursayans are tired of the usual interview, they are reluctant to speak once again under the same circumstances. Although we cannot promise change we can promise a different register and outlook in terms of representation, they agree to take part.

Omnia Khalil joins us on a scorching afternoon: Omnia has been toiling in Ramlat Boulaq for years, a neighbourhood to the North of Qursaya under the same predicament and thinks the two parties have not yet met to discuss and possibly unite their struggles. Omnia describes her efforts as an architect, planning the neighbourhood with the residents of Ramlat and presenting their plans to the ministry. I am in awe as she speaks in detail of the Nile City Towers and their intricate relationship with the residents of Ramlat, both as a provider of labour (the towers are serviced by many who live at their feet, in the informal, sprawling neighbourhood), and as a usurper of land- plans for the towers to expand under Cairo 2050 have put Ramlat at risk of erasure for years. Looking at her bird's eye view plans of Ramlat, I come to think that an overall plan of the neighbourhoods may be a thought-provoking tool to use.

I spend the next 2 weeks sticking my fingers together with superglue, cutting buildings out of foam board, painting milk cartons to produce a rudimentary maquette of the future city in its clumsy vulgarity of fake glass and steel. The maquette is a prop; through its unfinished edges, its unprecious appearance, it lends itself to being messed with.

While I work on the maquette, I think of Michael Taussig's 'My Cocaine Museum', where the anthropologist describes the conquistadores' journeys through the Rio Timbiqui and their failed attempts to map it. The murky, snaking waters and torrid conditions kill most of the watercolourists on board. The colonisers decide then to hire a local artists to work on the boats, but the locals have no conception or interest in the 'bird's eye view' so their drawings become surreal representations of scenes that they came across on foot, landmarks and riverbends that the colonizers cannot interpret.

We meticulously prepare the workshop. Nalzy and I work on contextual documents with Omnia's help, translating parts of the legislation, while Selma takes care of production- the sound, the meals, tripods, extra crew.

In early November, a few days before the shoot, we hold a crisis meeting. Nazly and Salma are panic-stricken; they have caught wind of a new law will come into force on the 10th of November, and it could jeopardize lives, as well as months of work. The law states that any Egyptian national receiving funds from a non-registered organisation supported by foreign institutions could face jail-terms, or even the death penalty. While the law does not necessarily apply to our case, recent arrests of friends and activists have alerted all to the far-reaching and twisted arms of the State. We decide to shoot earlier to avoid possible persecution.

On the day of the shoot we pull through, somewhat unprepared, on edge, with trembling hands. The shaking is transmitted to the shots.

The next few weeks are dedicated to editing the footage with Salma in Mosireen's studio. Mosireen, the political film collective, has ceased to actively use their space, the editing suite lies dormant, the computers are quiet, dusty, in a room at the back of the apartment. Salma describes the activities of the collective: international conferences and screenings, debates and pre-protest preparation. Speaking, she scans the now vacant rooms pointing out to where people sat, where people spoke. We work in 6-8 hour time-slots, often staying up past 2am, lights off, with the hum of the computer tower as a constant.

On November the 29th I am alone at the editing desk when I hear loud explosions and cries, I stick my head out of window without fully opening the blinds, just enough to catch a glimpse of Talaat Harb dotted with protestors heading to Tahrir. Tanks with swaying turrets and armoured jeeps speed through the street, trying to disperse the crowds. Soon the entire block, up to the 5th floor of my building, is wrapped-thick in tear gas. My phone starts to beep, it's Jasmina texting me to not, under any circumstance, leave the apartment. Lock the door. Double lock the door. And stay put. Mubarak had just been released without charges, yet another blow to the bent-double, battered body of the revolution. As always, but especially under these circumstances, you have to ask yourself what and who you are working for, and the answer doesn't come easy.

Subsequently the film is presented in Cairo, at Beirut, and a few months later at Casco, in the Netherlands. In these two spaces the film's intent hovers ghost-like in different ways. In Cairo, I tried and failed to mobilize neighbourhood screenings in Ramlat and Qursaya in the weeks prior to my departure. The pressure had mounted too much. With the law in effect, all parties involved agreed that screenings were a dangerous idea. I did manage to smuggle copies of the film to those involved, but it felt like a broken promise, a consolation prize, far from a victory. In the Netherlands, luckily, the film does not seem to read as reductive. The work appears to breach the notion of a testimony and attest itself as a recording of an event in local momentum-building, yet how much momentum can you build trapped in the straightjacket of representation? A representation that cannot circulate, a truncated sentence, a solitary revere?

About the artist

Adelita Husni-Bey is an artist and researcher. Born to an Italian journalist and a Libyan architect in 1985, Adelita studied Fine Art at Chelsea School of Arts and Photography and Sociology at Goldsmiths University. Her practice, which encompasses drawing, painting, collage, video, and participatory workshops, concentrates on micro-utopias, and on how collective memory works, as well as questioning the mechanisms of political and economic power and control.

Her background in sociology as well as fine arts aided her in her critique of prevailing systems of organization of advanced capitalist societies, in areas such as labour, schooling and housing. She questions the type of visibility present in the production of artwork about 'under-represented communities' and looks for alternatives, as a form of reaction to the way Western society is structured. In that sense, her role as an artist strives to instigate reflection on, and effectively produce, alternative social imaginaries.

Recent projects have also focused on unearthing and re-thinking radical pedagogical models within the framework of anarcho-collectivist studies. Her solo shows have included The Green Mountain, ViaFarini/DOCVA, 2010, Deadmouth at Galleria Laveronica, 2010, Playing Truant, Gasworks, 2012. Selected group shows include: TRACK, S.M.A.K museum, 2012, Mental Furniture Industry, Flattime House, London, 2013, Jens, Hordeland Kunstsenter, 2013, Meeting Points 7, MuKHa, Antwerp, 2013, 0 Degree Performance, Moscow Biennial 2013, What is an Institution? Beirut Season 4, Cairo, 2013, We Have Never Been Modern, Songeun Art Space, Seoul, 2014, Giving Contour to Shadows, Neue Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin, 2014, Utopia for Sale?, Maxxi Museum, Rome. She has been featured in International Art-related press such as Flash art, Modern Painters, Ibraaz, Mousee Magazine and Frieze, as well as international newspapers The Guardian and Corriere Della Sera. She has recently completed the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York and is working with Italian schools to foster a critical understanding of the economic crisis by teenage students.