"There are people whom upon meeting with them, you feel like you've met with yourself"

Ghada Al-Samman

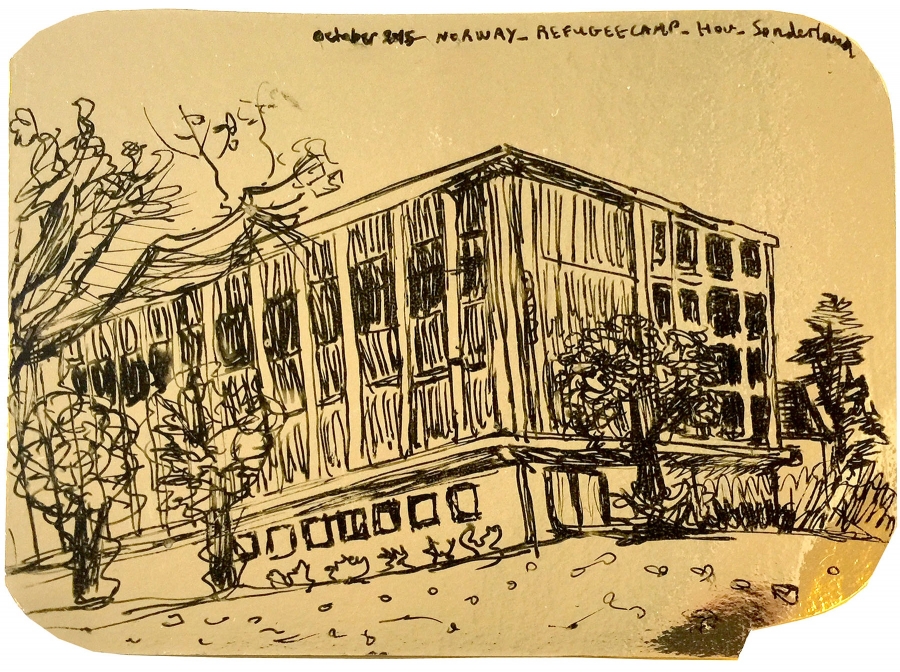

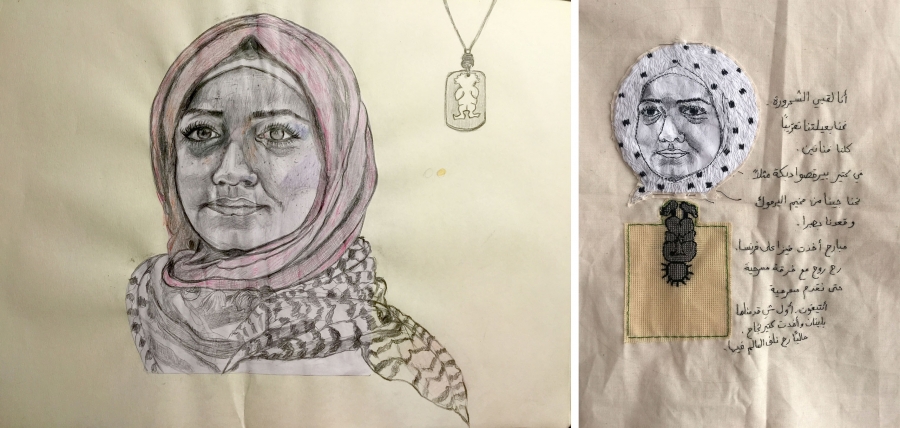

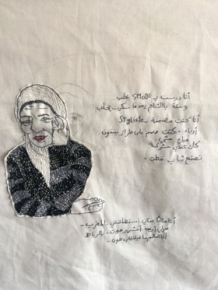

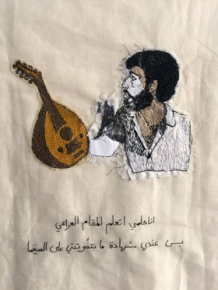

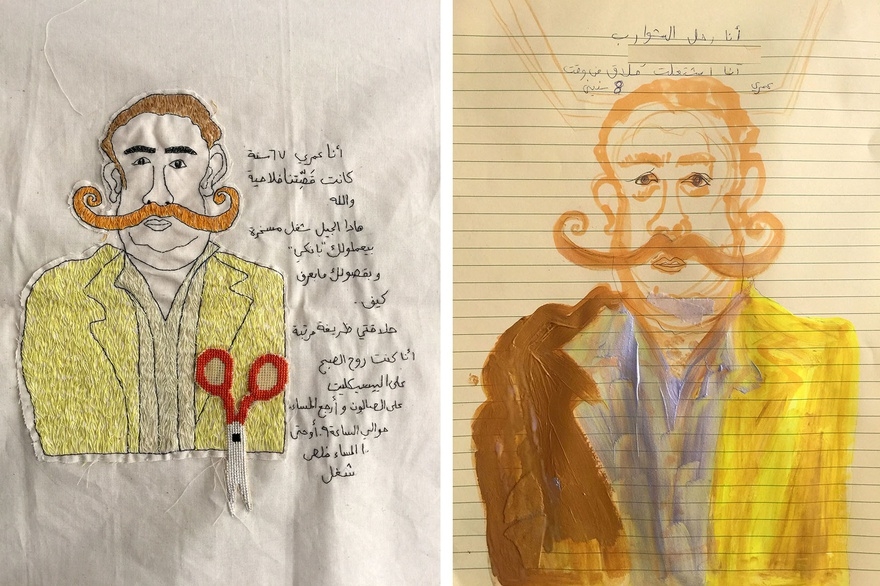

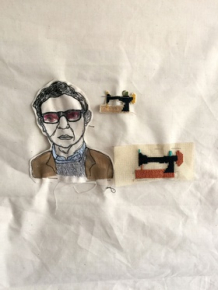

For the next 150 works of "I Strongly Believe in Our Right To Be Frivolous", I am carrying out an embroidery project, in an attempt to emotionally bring scattered Syrian families, individuals and friends back together and as a way to embroider for each person, her or his dreams and aspirations. The most important aspect of the work is about meeting with all those people, sketching them and writing down our conversations and thus recording our encounter. Although not explicitly about the crisis, the encounter is a witness to it and to life in Syria before 2011. Many of the individuals I have met in Beirut have now departed to Europe by sea or by plane. I would like to meet with them or with their family members in their newly settled environments and record once again our encounters by sketching and taking notes. Those sketches and notes will then be transformed into stitched works.

By doing this, I would like to think that embroidering is about bringing people, ideas, important elements and objects together. The tool is simply a needle and a thread of whichever fascinating color you may choose. You can bring anything you want and stitch it to something else. Stitching is also forming, not only you can bring things together, but you can make them exist, they will be stitched on an off white cotton surface. I don't really care about the stitching technique or method; I prefer chaos in stitching, and using it as a way of expression in this case, or as I mentioned earlier, to bring things together and to witness the "un-witnessable." It is not about commemorating a region through its stitching styles and nor the "identity" of any embroidering style.

I plan to transform the drawings into sewed portraits, with added embroidered objects, sewed sentences and thoughts, even fictional aspirations and narratives, whenever possible. A thread's path, pierced by a needle, even if chaotic, creates some order, because it is repetitive, thus helping that witnessing process to exist. Witnessing is about being present in a place, at the same time of the incident that we witness. In the same way, a thread has to run straightaway to the next point directed by the needle. As Fatima Mernissi suggests, embroidering helps foster women's aspirations: by leaving a space for their imagination to flow, it not only helps them embroider their repressed wishes but allows them when they're embroidering together to discuss them and dream about their unrealized ambitions. Many women I have met come from rather peasant-like backgrounds, either from Rif of Damascus, such as Wadi Barada, or Rif Homs, Rif Halab or Hama, from Deir-El Zor, or small towns on the border with Turkey. Those women in particular according to the groups I have met, content themselves to live with very little means, not hoping for anything else than a newborn baby once every year or two. When the war started, and their homes were destroyed, these women were left with nothing. The large house with green spaces around it, which formed "their stronghold" have all been lost., their parents and their neighbors have all been lost! I reckon that sooner or later their basic survival needs and ethics will be going through big question marks. The men continue to work in Beirut like before, the only difference is that they are now "united" with their wives and live as couples in Lebanon under very hard conditions still.

There is another example, and I would like to mention here. I met an amazing woman from Homs, Um Mohammad. Her husband who worked as an engineer is now retired. She told me that right before 2011, she was finally able to find everything she needed in her kitchen and that with her husband they managed to buy two houses, after a lot of years of saving. So they had a flat in the city and a house in the village.

— " I could finally find everything I need in my kitchen,

ask me, what do you wish to have?

I would open a closet and find it for you."

I was very touched by that, and thought that this is actually a great scale to measure our "happiness". Are you really able to buy everything you need for your kitchen?

Um Mohammad has currently lost all the houses, and now the few people left in her town are going through hunger, isolation, no medicine, no water, etc…

She currently stays in Sabra and Shatila camp with her family members, waiting for some ceasefire to return home. She is against fleeing by sea to Europe and won't allow her children or husband to do so. I really have deep respect for her ethics and her skills of survival. She keeps her tiny house now in Sabra and Shatila very neat and clean. When I visit her, I feel I want to stay there forever, because of the peaceful energy she spreads around with all her family members.

In order to achieve those 150 embroideries, I am inviting women like Um Mohammad to work with me and to help me sew over the portraits of the people I sketched or objects that they desire to be portrayed with. We form circles and work together in my studio whenever possible. It becomes like a job for the women. I wish I could "employ" them everyday but my means are limited and my rhythm is proving slower than I expected. Each portrait needs a lot of thinking before realizing it and before I can decide what to write for that person or what to add as objects around her/him. Each embroidered portrait is about a persona, it has to make sense, even if sometimes I decide to fictionalize some elements. Plus, when you embroider, you need to be minimal, the amount of work has to make sense. And before giving work to the women, I have to be very clear on what I want, and I have to encourage them to be more chaotic in their sewing style.

At times I visit them at home to bring them more work and on some occasions I would meet with their family members who would also ask me to sketch them, and so I do. It is hard for me to meet someone I don't know very well and to come up with an interesting portrait, it is intimidating as well to portray someone you hardly know, I try not to do that, I am incapable to make a good portrait in this sense. Meeting several times with each person I draw is crucial and more important than meeting other family members and drawing them.

I am drawing many people who have fled out of Syria, but not all of them are refugees. Many who are in Beirut still visit their towns in Syria from time to time. For instance, they prefer to visit their doctors there, since in Lebanon it is so expensive, while in Syria it is almost free, so for those who are not directly in danger or wanted and if it's possible to reach their cities or towns, they still try to visit their parents, go to doctors there, renew their papers, etc…

This work is allowing me to meet with various people from various backgrounds, people with different beliefs, social classes, languages and faces. What is amazing and what is common between them all, or what I like to see in them, is their resilience. As someone who grew up in the war, I am very interested to keep on witnessing how people no matter what happens, try to build up their lives again, and without giving up. I have always been more interested to see aspects of survival, in parallel to wars. And recently, I promised myself, that the texts on the embroideries should reveal such resilience. The first ten I did were not focused on that aspect yet, but it's only by making them that I understood what I really wanted.

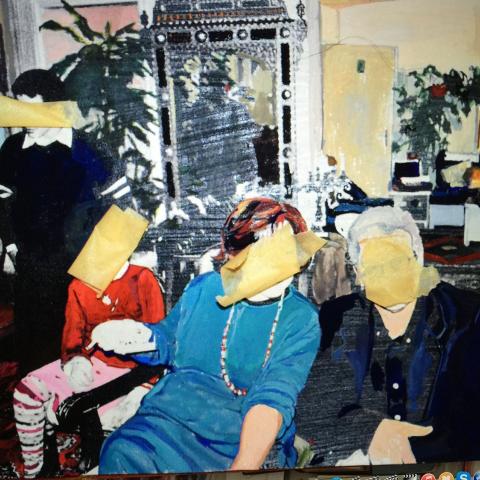

In November 2015, I hosted a lunch for a group of forty-two people, consisting of women with their children or women with their grandchildren (in this case the children were orphans) and then we were received for a lunch by Kanza wa Sunbula, a Lebanese local program that supports people with special needs.

The two groups mingled for a day in a new location where Kanza wa Sunbula are based in a mountainous town surrounded by pine trees in Lebanon.

The encounter between the two groups took shape in dancing and singing, the children were offered some facial disguise, and thus we played. I also documented that day, and filmed each family separately. It was impossible to host 42 people, and to draw them at the same time. Because I have them documented in videos, I am now capable of making rather realistic drawings which might form the chore of the upcoming 150 new drawings after I finish the embroidered ones.

The group came together in collaboration with the Syrian association Basma & Zeitouna whose Beirut branch is based in Sabra and Shatila camp. With their help, we gathered all the families from Sabra and Shatila in Broumana. This was a nice day out for them.

There are about 12,000 Syrian families who were forced to settle in the camp because of the war. Some of them are Syrians who fled the Yarmouk camp, so in fact they are originally Palestinians, who were born and raised in Syria. At Sabra and Shatila the conditions are very hard, the Palestinians living there for decades ago continue to live under difficult conditions.

The "new comers" Syrians (including the "Palestinians' Syrians") all hope to leave as soon as they can. At night they often witness shootings, from various competing factions in the area. More often than not, electricity and water cuts occur.

Many of these women are hoping to leave Lebanon, ideally to return to their home countries or to join their husbands in Europe, after they have left by sea. As far as I know, some families were "taken in" by the Canadian state, it is the case of an amazing woman I met from Kobani who speaks Kurdish, Turkish and Arabic. I made her drawing with her two daughters and she asked me to embroider the Kurdish flag.

Here I am attaching some pictures to show some of the embroidered portraits, some pictures from our encounter during the lunch day and others from my studio while working collaboratively with Um Abdo and Um Mohammad.

I would like to thank Rania Jaber for discussing with me over and over the conceptual details of this work and helping me clarify and develop many aspects of it. My deepest gratitude to Ghassan Hammash, Sari Moustapha, Julia Jamal, Nivine Diab Sukkari, Israa Shahrour and Mona Fattaleh for helping me connect with many people and realize the Basma & Zeitouna lunch day. I would also like to thank Hanan Bdeir el Solh, Ritta Maalouf, Nadia Kharrat, Chadia Maqsad, Reva Fneiche, as well as all Kanza wa Sunbula team and residents and Al Amal Institute for the Disabled for hosting the families for a day at their new location in Broumana. On that day, Firas Hallak's moral support and concentration behind the camera, documenting what was happening was of utmost importance, I am so thankful to him.

I am as well very grateful for Nesrie Khodre, for allowing me to use her father's office at Raouche, to appropriate it as my studio and work there to realize many of those portraits and embroideries. Furthermore, I would like to mention and thank all the women who have helped me so far realize the embroideries, Um Mahmoud, Um Abdo, Um Israa, and Um Joumaa. I am as well really thankful that many people have had the patience and acceptance to be portrayed by me. Without their patience and their openness to my work, I could not do any of the portraits.

I am also deeply grateful to Mofradat (previously YATF) and the Kamel Lazaar Foundation for supporting my project and helping me gradually realise it. Further thanks are to Mondriaan Fund in the Netherlands, for supporting my art practice while I work on this project.

And I am still looking for more support to continue this work.

"O inhabitants of my song: trust in water" and I sleep pierced and crowned by my tomorrow…

I dreamed the earth's heart is greater than its map, more clear than its mirrors and my gallows.

"Now As You Awaken", Mahmoud Darwish, translated from the Arabic by Omnia Amin and Rick London.

About the artist

Mounira Al Solh's visual practice embraces video, painting, embroidery and performance. Integration of social and political themes grounded in daily life are reflected in research, as well as in production and presentation of work and in the role of the investigative organizer Mounira has. Al Solh's art aspires to ask large questions in small places, operating according to Ginzburg's notion of microhistory. Humor is surprisingly an integral part of the artist's work, concealing trauma in laughter as a way to process it.

As the editor of NOA (Not Only Arabic) magazine, a performative gesture co-edited with collaborators such as Jacques Aswad and Mona Abu Rayyan, and of NOA language school (with Angela Serino), Al Solh examines topics such as treason, arrest, fragmentation of language and schizophrenia in dialogue with artists and writers.

Her work has been displayed in exhibitions at the Venice Biennale, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut; Kunsthalle Lisbon, Portugal; Art in General, New York; Lebanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennial; Homeworks, Beirut; The New Museum, New York; Haus Der Kunst, Munich; Manifesta 8, Murcia, Spain; The Guild Art Gallery, Mumbai; Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Al Riwaq Art Space, Manama, Bahrain; Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin and the 11th International Istanbul Biennial.

In 2003 she was awarded the Kentertainment Painting Prize in Lebanon and her video Rawane's Song received the 2007 jury prize at VideoBrasil. She is Uriot Prize winner at the Rijksakademie, and was nominated for the Volkskrant Award in the Netherlands in 2009. Most recently she has been shortlisted for the Abraaj Group Art Prize, 2015.

Mounira Al Solh studied painting at the Lebanese University in Beirut (LB), and Fine Arts at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam (NL), where she was also research resident at the Rijksakademie in 2007 and 2008.

Al Solh teaches as a guest in various art schools in the Netherlands and in Beirut, and she is represented by Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut & Hamburg. She lives and works between Amsterdam and Beirut.