The current phase of Learning Not to Dream centres on the translation, subtitling, and proofing of Kassem Hawal's 35-minute 1982 documentary Massacre: Sabra and Shatila. Parallel to these technical processes, research into the film's making continues in collaboration with the director. The project's completion will unite these strands: delivering a digitally preserved edition of the film; an accompanying director's filmography/ biography; and a research essay treating the film's historic and aesthetic significances.

The Palestine Film Foundation conducted a digital scan of a surviving analogue tape of Massacre in the summer of 2014. Translations of the film's Arabic, English, and Hebrew dialogue were prepared in order to generate English and Arabic subtitles. A draft of the English subtitles has now been created, with synchronisation adjustments underway. Once Arabic subtitles are added and proofing carried out, a final dual subtitle edition of the film will be produced. Exhibition is anticipated from Spring 2015.

What follows here is a set of initial empirical and reflective notes on the film and its making. Kassem Hawal's recollections of the period surrounding the film are first accompanied by a brief chronology of his cultural activism during that time. A discussion of survivor testimonies in Massacre: Sabra and Shatila follows, along with short excerpts from the working draft of the subtitled film (and transcript). The film is not assessed in its entirety: Its crucial final chapter is noted, but will be addressed in detail only once the project is complete.

Recollections / Chronology

For me, I look back and see it all, for myself, as a period in history, a period in my life. But I don't have the same connection or the same feeling that I know I had at that time.

Back at that time, I was working in a tough situation – there was never any money for the film work, which meant making things of a low technical quality. So even then I felt 'this is not my dream'. But at the same time, I knew there was no other place to be, no other place like that – I'd found the Palestinian people I met were a very beautiful people, and that in the Revolution we all felt that we could change the world.

But, in the end, it was the world that changed us.

—Kassem Hawal, correspondence, June 2014

Facing persecution for political writing, Kassem Hawal left Iraq in 1970, aiming to enter the British-ruled UAE (then know as the 'Trucial States'). Because a visa application in Baghdad risked attracting the attention of Iraqi security agencies, he went first to Beirut to apply at the British Embassy before continuing his journey. In Lebanon though, Hawal met Ghassan Kanafani, a fellow writer and kindred spirit. The two became close; Kanafani asked Hawal to stay and join him at the PFLP's Al-Hadaf magazine to edit a culture section the two had discussed.

From late 1970, Hawal was active in the PFLP's cultural programmes, working on Al-Hadaf, and in theatre projects within the refugee camps. With comrades, and in editorials for Al-Hadaf, he agitated for investment in film production. At first, this was resisted as a costly and potentially elitist deviation from the more grassroots, participatory arts that the movement was predisposed toward. Nevertheless, funds were eventually allocated, and from 1971 to 1974, the PFLP completed five short films, four directed by Hawal. One of these paid homage to his friend, murdered by Israeli forces in 1972: Ghassan Kanafani: The Word-Gun (Ghassan Kanafani: Al Kalima Boundouqiyah).

We filmed the reality of the Palestinian revolution in every aspect, whether the political, military, social, economic, or cultural. We documented all this, though we were just a small group of filmmakers with technically poor film and still cameras. We couldn't produce a 'higher quality' cinema to match the standard of 'normal film' with its expressive language, because a 'poor, weak hand' can't always carry a camera that needs a 'golden hand' to realise its full cinematic dream.

But the most important thing is that we did produce film documents (and still photographic documents), much of which was lost with what was taken by Israeli soldiers in 1982 when Israel invaded Beirut and forced the Palestinian Revolution out. Between that great loss and those who have since misrepresented or distorted the depiction of filmmaking in this time, a great deal of the truth that was once documented with brave cameras has vanished.

Of my own lost work, I remember in particular: filming frequently in the tunnel systems built under the camps; I filmed an underground military academy; and I took my Bolex to south Lebanon in 1978 to face the Israeli invasion in Tebnin and Tsur; I filmed towns and cities deserted of their people…

—Kassem Hawal, correspondence, May 2014

Hawal's 1974 film-poem Our Small Houses is one of the few works of this period known to survive. Merging Marxist-Leninist analysis with oneiric visions of war and play, the film won the Silver Medal at the 1974 Leipzig Festival. Soon afterward, Hawal returned to Iraq, making several shorts including The Marshes (1976), examining the heritage of Marsh Arabs in his native Basra district.

Hawal returned to Lebanon in 1978, beginning work on what remains his best-known film: an adaptation of Kanafani's novella, Return to Haifa. This was finished in 1982, just months before the Israeli invasion brought the Palestinian revolution in Lebanon to a violent end. In the years that followed, Hawal moved from Syria to Greece and to Holland, where he now lives.

For me today, an Iraqi emigrant living in Holland, that period of my life is gone but never forgotten.

I learnt from the Palestinian Revolution two things: patience and courage. I lived with a beautiful dreamy people. But I also learned not to dream like that again. After waking up from our 'long nap', we discovered that we were living a dream bigger than the small area where we lived – a space that contained great people and dreams but was in the end just a few square kilometers… kilometres that included the camps of Sabra and Shatila.

—Kassem Hawal, correspondence, May 2014

Massacre: Sabra and Shatila

In summer 1982, Hawal began work on a film funded by the Arab League in response to Israel's sacking of Palestinian cultural and historical resources in Beirut (completed as The Palestinian Identity in 1984). When the Sabra and Shatila massacre took place on the weekend of September 16th–18th, he suspended this project to divert the remaining funds into an urgent film on the atrocities. Massacre: Sabra and Shatila was finished in 1982 with additional post-production financing from the Libyan Ministry of Culture (in return for a production credit). It was the first film made on the massacre.

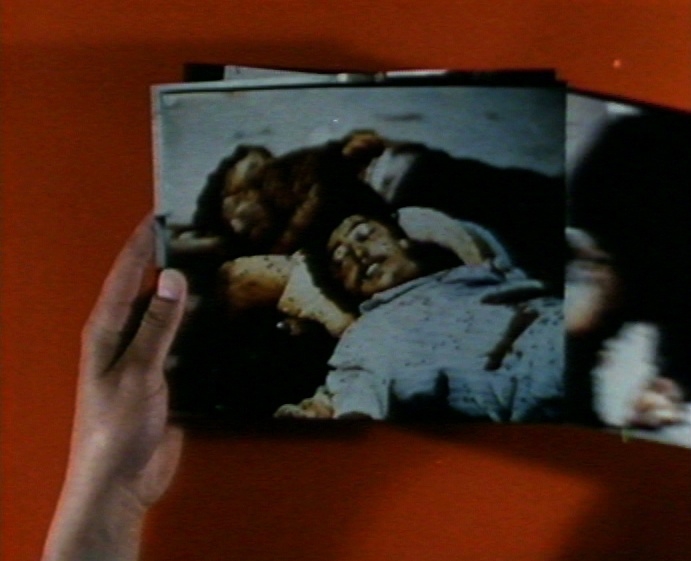

Massacre draws on survivor testimonies to generate a portrait of savagery and trauma. The proximity of the events recounted by survivors makes theirs a painfully compelling field of testimony. By adding footage shot in the wake of the massacre, the film arrives at a gruesome evidentiary whole: searing testimonies are allied with 'crime-scene' images evidencing carnage and cruelty. To a certain degree, Massacre can be read through such a juridical lens – as a work of prosecutorial cinema. Concise, at 35 minutes in length, its main 'body of proof' in this sense lies in a core 20-minute block of witness statements. However, these are not arrayed in the calculated manner one might expect of a straightforward exposé. On the contrary, these testimonies are so rapidly delivered and densely interwoven as to attain a cumulative affective force that goes beyond any end in rational persuasion. Each account of barbarity seems to exceed and overlap the last, conjuring a nightmarish episodic account of the massacre itself as well as a vivid impression of the psychological trauma involved in its remembering.

Massacre's title sequence recalls the opening passage of another work completed after the devastation of 1982 – Muhammad Malas's The Dream (completed in 1987). By returning to footage he had shot before 1982 and prior to the 1985 War of the Camps, Malas looked to 'the pre-1982 life of the camps as a means of imbuing the desperate present of the mid- and late-1980s with hope'.[1] His film engaged this past obliquely – via the often-strange, fragmentary dreams that had been recounted to Malas by interviewees in 1981.

In an opening passage of The Dream, a hand-held camera transports the viewer along the narrow lanes of a refugee camp, arriving at the inner courtyard of a family home. The sounds of a lullaby accompany the sequence. As Nadia Yaqub observes, the composition evokes that journey toward a 'psychological interior that is the focus of The Dream'[2]. In Massacre's opening passage, this movement toward an interior is more erratic; the camera seems to stagger warily rather than glide ahead. The camp is eerily emptied of life. Blood red title cards punctuate the sequence. Kawkab Hamza's detuned oud composition lends an ominous sense of what has occurred, and what is to come.

None of the survivors featured in Massacre is identified by name. All but one is interviewed in the camps, some at the very locations to which their testimonies refer. The only exception is the young woman featured in the excerpts above, who spoke with Hawal in Tripoli, Libya, after being reunited with family there after the massacre. Like many of the survivor testimonies in the film, there is a hallucinatory quality to her account. The site of the massacre is revisited in grotesque tableaus, each recalled as 'scenes' so 'weird and unimaginable' they can barely be rendered into words. Indeed, the inadequacy of language becomes paradoxically key to the testimony's power to simultaneously bear witness to the atrocities and to the agonies of witnessing itself.

The immediacy of the scenes recalled seems to combine with their perversity to engender a distinct traumatic syntax: tenses slip, the past returns, the dead live again, and grim realities grow increasingly surreal. In the following excerpt from the project's working subtitle text, an elderly Lebanese woman recalls searching the camp for her family.

Excerpt from working English translation, Massacre: Sabra and Shatila, 1982, Kassem Hawal. 00:18:26–00:20:04. Translation (draft version) by the Palestine Film Foundation.

I searched for my husband and my son in the place where they took them. They took them somewhere... and they put them... and they killed them in the pickup.

The pickup has a chain.

They dragged… they killed my son and Deeb El-Hinnawi, and Mohammed El Kharasani. They put my son under the pickup. He was wearing a white shirt, white shoes and jeans.

And my husband has his I.D. and his cigarette box in his hand.

Sleeping ... as if he's praying.

[…]

My daughter came and looked at her father and said: "Oh, mother, it's father! It's my brother-in-law, mother! I know this one, and this one..."

She was screaming so much, she looked strange: her eyes were popping out.

Conclusion

Across the testimonies at the core of Massacre, neither anger nor sadness prevail so much as this overarching sense of an uncanny spectacle – incomprehensible in its barbarity, surely; but also simply strange … other-worldly. In this, the film continues to 'recall' Malas's The Dream of four years later. As survivors recount sights that are as inexpressible as they are indelible, like Malas's dreamers, they perform the ineffable into a series of fractured episodes and lurid images. If Massacre's opening sequence introduces the camp's interior as eerily bereft of life, these fragmented testimonies re-populate that inner space with spectral apparitions of the dead and with the unutterable nightmares of the living.

In the final section of the film, this correspondence linking the film's spatial and its testimonial attributes will undergo a radical modulation: Massacre now descends into a subterranean prison beneath the Syrian desert, where Israeli prisoners-of-war furnish testimony of a very different order.

Learning Not to Dream will be completed in early 2015.

About the artist

The Palestine Film Foundation (PFF) is a London-based research and exhibition structure specialising in film and video work from and upon Palestine. Founded in 2004, the PFF manages a range of film preservation, subtitling, education, and programming activities in the UK, including the annual London Palestine Film Festival.

This project will be conducted by the PFF's co-director, Nick Denes, who leads the PFF's research and preservation programme. Denes is a film curator and sociologist. He is Senior Teaching Fellow in the Centre for Media and Film Studies, SOAS, University of London, and has published widely on moving images of and from Palestine, the 'new far right' in the contemporary EU, and surveillance in Palestine/Israel.